To anyone paying attention, this week in America was unrelenting.

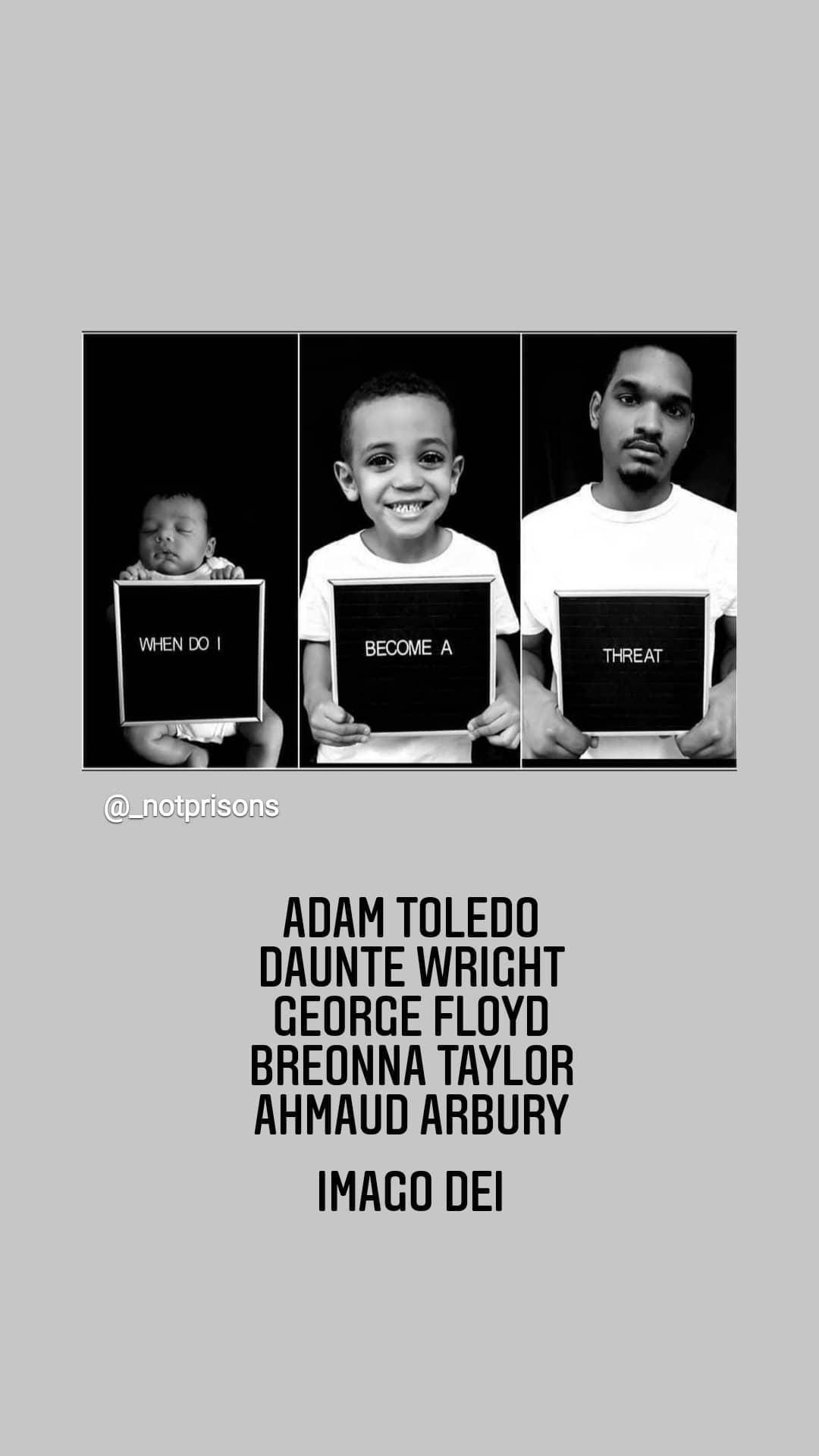

The trial of Derek Chauvin is happening in Minneapolis, just less than a year since the murder of George Floyd. It is undoubtedly stirring painful emotions and difficult conversations.

Then, on Wednesday, police released bodycam footage of Chicago police shooting 13-year-old Adam Toledo in the chest as he, following orders, faced them and put his hands up. Anguish, outrage, and more grief followed.

Finally, Thursday night brought the third mass shooting in Indianapolis of 2021. A former employee apparently opened fire indiscriminately at a FedEx facility, killing eight people and injuring more. The shooter apparently had his shotguns seized from him in March of 2020 due to mental conditions and being deemed a “dangerous person,” but he was able to successfully and legally purchase two semiautomatic rifles months later. These were the weapons he used Thursday night.

Any sense of relief from the constant drumbeat of gun violence and mass shootings during 2020 has been long forgotten.

America, we have a massive, willful gun problem and these 16 maps and charts show the extent to which we stand alone in the world with this problem that we’ve created and refuse to deal with in any meaningful way.

While the cycle of shooting–grief-outrage-complacency is the collective cycle, this week I found myself thinking back to a group of kids I worked with almost twenty years ago. Taking a break from college in the early 2000s, I worked at a local non-profit that was described as a “residential treatment facility for at-risk youth.” It had an emergency shelter for suddenly homeless kids all the way up to a fully secure building for those who had demonstrated themselves as a threat to others or their own well-being.

While some came to this facility as a pit stop between being removed from a dangerous or harmful environment and being placed with a safe, trusted relative or a foster home, it was also a place for those who had experienced significant emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. They were there to receive 24/7 care, treatment, and monitoring. Some residents had committed their own crimes, while others, at no fault of their own, had been hurt in visible or invisible ways and needed help figuring out how to cope with the trauma and wounds inflicted upon them.

I specifically worked in a residence with boys aged six to thirteen, all of who had experienced physical, emotional, or sexual abuse.

Nothing could really have prepared me fully for the 18 months I would spend supervising, teaching, restraining, documenting, and protecting nearly 50 kids who had experienced the darkest, hardest, most anguishing stories I’ve ever heard.

The hope with each of them was to restore them to a safe, supportive environment. That might be a grandparent who had finally convinced a judge they would be able to provide adequate care and supervision or it could be a foster home that had opened up to give them something closer to a steady family home to grow up in. Many of them had no hopes of reconnecting with their parents, seeing as they were in prison or had chosen to terminate their parental rights, making the kids wards of the state.

Over time, most of the cumulative 50 kids I worked with moved out and we almost never heard anything else. We invested in, cared for, supervised, and poured everything we had into these kids, hoping that the time they spent in the program, whether it was a month or multiple years, would make a difference.

Fast forward ten years and I was at my in-law’s house, visiting for the holidays. We had a nice dinner, shared stories of past gatherings, and were sitting on the couch enjoying some quiet after the kids had gone to bed.

The local news had come on and we decided to watch a little bit before going to bed. A few stories in, the news anchor began to tell the story of a double murder that had taken place. The man, the reporter shared, had been fired from his job for poor attendance. A few weeks later, he had come to the home of his former employer in the middle of the day, presumably to rob it, but encountered the man’s wife and daughter. He murdered them in their home.

It was a horrifying story in the relatively quiet and peaceful neighborhood where it happened. The reporter continued to say that a suspect had been arrested and police were confident they had the man responsible for the heinous crime. Then they said his name and my stomach dropped.

The suspect was one of the kids I had worked with years earlier. His name was unique enough, there was little question it was the same person. Then the mug shot popped up on the screen and it removed any doubt. A little wider, more sculpted, but this was the same face of a resident who had been in my group for the full 18-months I worked there.

“What could we have done differently? Was there not anything else we could have done?” I asked these questions as I laid down, trying to get to sleep that night. I wasn’t asking them expecting to find any real answer, because I knew how much trauma this particular kid had experienced.

I knew his family history, his poor academic performance, all of the diagnoses related to mental illness, the suspicion of brain damage from the physical abuse he had endured. More than anything, I grieved that he would now be locked up in prison for the rest of his life, adding to the count of lives lost because of this murder.

Still, to this day, any time I catch a glimpse of local news, I worry that I’ll see the name or face of another resident who wasn’t able to escape the systemic, unique, learned, and natural disadvantages that have haunted their steps for years and years and years.

I don’t have a neat way to wrap up this story. What I will say though is that we can’t just keep reading stories of violence, death, and anguish without doing anything.

We need concrete action to stem the tide of gun violence in America.

We need real, substantive accountability for police violence.

We need concrete action to invest in highly accessible mental health resources at a local, state, and national level. For those who are grieving or traumatized, they need support and healing. For those who discharge their own pain and inflict suffering, they too, deserve support for their mental health.

When it comes to gun violence and when it comes to mental health, we are getting a combination of what we have created and what we allow. In significant ways, it’s a choice.

We can create better ways and we do not have to continue to allow what has become normal to extend into the future.

Links to Check Out

Podcast: Flying Coach with Steve Kerr and Pete Caroll: Senator Corey Booker

Podcast: Radiolab: What Up Holmes?

Podcast: WorkLife with Adam Grant: The Science of Productive Conflict

Movie: The Trial of the Chicago 7

Movie: In case you haven’t seen it, the trailer for Space Jam 2

Article: The Anatomy of a Commitment

Article: Meet the Nepalese climbers who removed 2.2 tons of rubbish from Everest while the tourists were away

Music: A new Lake Street Dive album

And finally, some good news on the vaccination front…